Content Disclaimer: Brief Discussions of Violence and War Atrocities

The primary subject of this article is the proliferation of Medieval Marxist historiography and its potential to include several certain historical inaccuracies. We will be primarily focusing on the work of R.H Hilton, a prominent Marxist Historian whom you will be well acquainted with by the end of this piece. We will then explore the historical inaccuracies of Hilton and why academics in his field are excellent punching bags in Monty Python’s Spamalot.

Now, before we commence, it is imperative to discuss why we are bringing up Marxist Historians. In our show, the characters of Dennis and his Mother are members of an “anarcho-syndicalist commune” which is hilariously historically inaccurate since such terminology was not used during that time. Their vocabulary feels wacky and out of place.

Image Source: Monty Python and the Quest for the Holy Grail

The Monty Python guys didn’t pull this ‘medieval socialist’ bit out of thin air, there is a large academic field specializing in a Marxian analysis of the Middle Ages. According to Medieval historian and enjoyer of Monty Python and the Quest for the Holy Grail John Alberth states:

“Some medieval historians, such as R.H. Hilton… do apply Marxist theory to the Middle Ages, particularly to the English Peasants' Revolt of 1381.” (Alberth, 26-27)

So, this will be the primary focus of this article, analyzing the work of Hilton and refuting some of his main arguments.

Image: Rodney Howard Hilton, Photographer Unknown

Politics and History (they go hand-in-hand!)

However, before we begin diving deep into the exciting world of Marxist historiography, it is imperative to mention the role of politics in history. Naturally, it is simply impossible to discern politics from history, the study of history has always been inextricably linked with politics, and there are some horrific examples of this such as the rewriting of the succession of the confederacy in the United States, denial of the Armenian Genocide, whitewashing of American and European colonization, War Crimes from Japan in WWII, and so many other horrific examples.

It is important to note that in this article, I am not making a political statement on the issue of Marxism I have specifically curated this article in a manner that doesn’t explicitly quote Marx or Hegel. We can discuss these historical inaccuracies without diving deep into the base/superstructure model because I don’t want to bore you to death. This is not an essay on Marxism and whether it is good or bad. That is up to you to decide your political path.

Rodney Howard Hilton & Dogmatism

Rodney Howard Hilton was an English Marxist historian, specializing in the transition from feudalism to capitalism in the late Middle Ages. Now what on Earth even is a Marxist Historian? In the lamest terms, he is an academic historian who primarily uses the concepts of historical materialism provided by Marx and uses a lens of the worker/owner dynamic in the majority of their analysis. This is an incredibly simplified version of Marxist historiography but it is enough to help you understand what is going on. Most Marxist historians can be classified into 4 different historical eras: ancient history, the middle ages, the 16th and 17th centuries, and modern history (Hilton, 11).

Image: Rodney Howard Hilton, Image Source: Philip Rahtz

One noticeable theme in Hilton’s writings about Marxist historiography is a concerning level of purity testing. He often writes about how a historian must dogmatically believe in everything Marx does and not doubt it. There cannot be an ounce of skepticism with this guy.

“The conversion into true Marxists of historians who claim to be Marxists will depend, of course, on the degree to which their consciousness has been liberated from the influence of bourgeois ideas, and on how long and how profoundly they have been studying Marxism.” (Hilton 12-3)

It is rather concerning to conclude that a true Marxist Historian is “liberated from the influence of bourgeois ideas” and that you can only be a historian of this type if you agree to their platitudes. The lack of skepticism and debate is wild in an otherwise academic field.

Core Tenants of the Marxist Historian

Moreover, the work of a Marxist historian was not merely to produce narratives from historical data and present them to the academic community, rather there were significantly different core tenants for these historians. According to Hilton, these were the primary tasks:

“Firstly, to help the labor movement, and especially the Marxist press, by writing articles on topical issues of current politics” (Hilton, 11)

In esscence, this means is that through Marxist-aligned publishing houses, the Marxist historian would write articles about current political events. Specifically, with the view that would best support labor organizing.

“Secondly, to make use of the knowledge and experience of the Marxist historians in the educational work conducted by workers’ organizations” (Hilton, 11)

Basically, Marxist Historians should have relationships with labor unions and not just sit in an ivory tower.

“Thirdly, to deepen, on the basis of Marxism, theoretical understanding both of the historical past and of current problems of the development of human society” (Hilton, 11)

This just means to apply a Marxist analysis of historical and current events.

“Fourthly, to contribute to the development of historical scholarship through academic research.” (Hilton, 11)

This just means that they should be actual historians. It is rather concerning when the actual job description of ‘historian’ is so low down on Hilton’s to-do list.

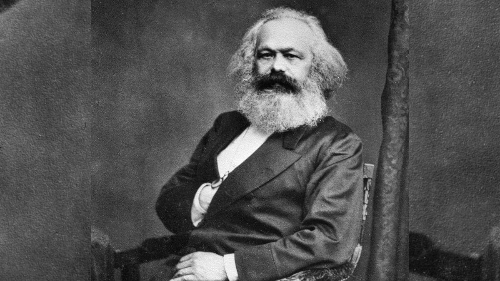

Image: Karl Marx

Now that we have gone through the basic concepts of Marxist historiography, we can now discuss Medieval Marxist historiography. Hilton states that most work done in this field is primarily concerned with the period of transition from a feudalist economy to a capitalist economy (Hilton 17). One important event, The Peasants Revolt of 1381 occurred during this transition. Now let's talk about this wacky and wild event!

The Peasants Revolt of 1381

The Peasants Revolt of 1381 was a series of organized attacks on politically active rich folks and institutions such as the Church and various academic institutions. This revolt occurred for ten days in June of 1381 and most violent events took place in Cambridgeshire. Historians have several theories as to why the peasants revolted and what were their goals. While it is important to note that when the leaders of these revolts gave demands, they were often long and seemingly appeared to just be listing grievances rather than having a single-minded mission. We will discuss this later on.

Image: "Depiction of the peasants’ revolt led by Wat Tyler in 1381. A meeting between Wat Tyler and the revolutionary priest John Ball is depicted. Detail, miniature of the fifteenth century by Jean Froissart. " Source: Jacobin

According to Hilton and other Marxist Historians, the Peasants Revolt of 1381 main mission was to abolish serfdom and promote human rights. He justifies this main cause in his article “Peasant Movements in England before 1381” in which he gives a series of examples of peasant protests through the legal system and through extrajudicial means that lay the groundwork for this revolt

Hilton’s Absurd Claims

One of Hilton’s examples of peasant activism for lack of a better term was in 1338 when a serf from the Prior of Tynemouth's manor of Elstwick was arrested for bringing animals on his lord’s land (Hilton, 129). Luckily for our serf, he was broken out of prison by some dude in Newcastle and after this prison breakout team did their first crime, they headed on over to Elstwick and held the manor under siege.

Now, I must admit, this is a pretty mental thing to do, breaking your friend out of jail and then taking the person who was wrongfully accused hostage is slightly rad. I am not condoning violence, but you must admit that it is rather poetic. Regardless, while this is a cool story, there is no evidence that the men who broke this serf out of prison did it out of freeing serfdom or for inequitable treatment.

Image: St. Michael's Church in Elstwick, England

There is a myriad of reasons why these men committed this action, maybe they were buddies with this serf, maybe the lord of Elstwick owed them money, and there are infinite reasons why this crime happened. It is dangerous to claim that they did it as a political statement against serfdom.

Moreover, another claim from Hilton is the fact that landowning peasants were very active members in organizing this revolt. This is indeed true, the vast majority of leaders in this revolt were small land-owners who had minor political influence or ‘rich peasants.’

“Rich peasants had little or no political influence, and for this reason we find them taking part in the Great Revolt. But some people were in the same position as the rich peasants as far as the labor problem was concerned, but who did have political influence.”

(Hilton 133)

Now the problem with this statement is that why would these rich peasants advocate for the abolition of serfdom? They were not serfs, they were able to control their land and hired laborers to work their fields. So their political interests do not align with the plight of the serfs and yet, they were the most prominent members of the peasant’s revolt.

Overall, we can see gaps in Hilton’s logic behind some of his claims that the Peasants Revolt of 1381 primary mission was to abolish serfdom. He uses a variety of wacky Marxist terminology that feels immensely out of place in a discussion about the Middle Ages and their motives. This is part one where we discussed the tenets of Marxist Historians. In the next article, using data from judicial records of those convicted in the Peasants Revolt of 1381, we will debunk Hilton’s claims and maybe even hear him whine about capitalism and see how his rhetoric is the inspiration for Dennis and Mrs. Galahad.

Works Cited

Hilton, Rodney H. "Peasant Movements in England before 1381" The Economic History Review, 1949, New Series, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1949), pp. 117- 136 https://www.jstor.org/stable/2590102

Hilton, Rodney H ‘The Work of English Marxist Historians in the Field of Medieval History' The Past and Present Society, Oxford, 2019 10.1093/pastj/gty050

Mingjie, Xu "Analysing the actions of the rebels in the English Revolt of 1381: The case of Cambridgeshire" The Economic History Review, November 2021 https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13122