There was never an official ‘code of chivalry’ that every single knight had to devote themselves to during the Middle Ages and the Crusades. However, there was a series of moral codes that went beyond the concepts of traditional combat. It introduced Chivalrous conduct, and ideal qualities of a knight such as “bravery, courtesy, honor, and gallantry toward women” (Alchin).

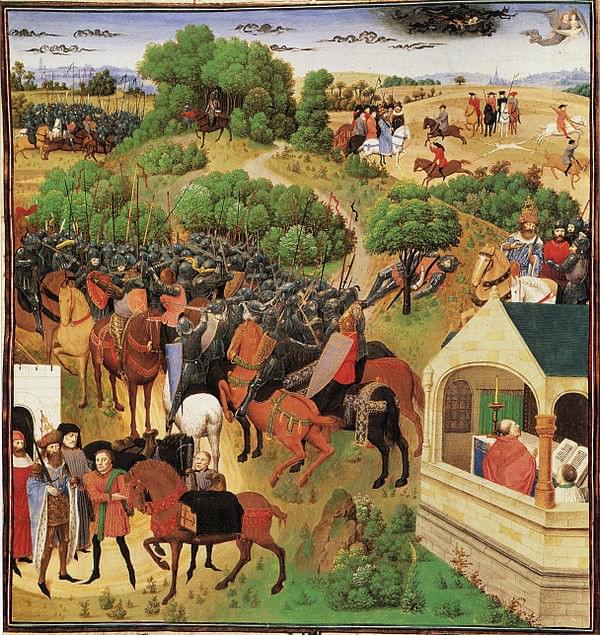

One of the primary and most important legends that speaks of a code of chivalry is in the ‘Song of Roland.’ This story follows the French knight Roland and other 8th-century Knights of the Dark Ages. The code in this song has been described as the “Charlemagne's Code of Chivalry.” Roland and his troops are betrayed at the hands of his family member, Ganelon, and are set up for failure (Owen). Regardless, Roland heads into battle, and even though the French are vastly outnumbered, for the honor of their Lord Charlemagne, they fight valiantly and Roland is eventually killed. The alleged actions that Roland took manifested in a code of conduct.

illustration by Simon Marmion from a manuscript of the Song of Roland, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

I will be going over 9 of the 17 (many of the entries are redundant and repetitive) of the entries of “Charlemagne's Code of Chivalry” and briefly mention where it shows up or the concept is subverted in our production of Spamalot.

1. To fear God and maintain His Church

This one is fairly simple, after the knights have their fun in Camelot, God is immensely pissed at Arthur and his crew and they all grovel at the sound of his voice. They go on the quest of the Grail to mainly get him off their back.

2. To serve the liege lord in valor and faith

This is more or less the same as the former entry, it essentially means to be a loyal servant to the Christian God. Technically, Arthur and his crew end up finding the grail (spoiler!) and rightfully serve their God by fulfilling their quest.

3. To protect the weak and defenseless

It would be safe to say that Lancelot does not abide by this rule. He kills the ‘I’m Not Dead Yet” Man, a person dying of the plague. He also murders 8 innocent weddinggoers in Swamp Castle.

4. To give succor to widows and orphans

This entry means to aid widows and orphans. There is not a single instance in this show where the Knights or Arthur assist a widow or an orphan. When Arthur meets Mrs. Galahad, he sweeps off with Dennis, leaving the widowed Mrs. Galahad completely alone.

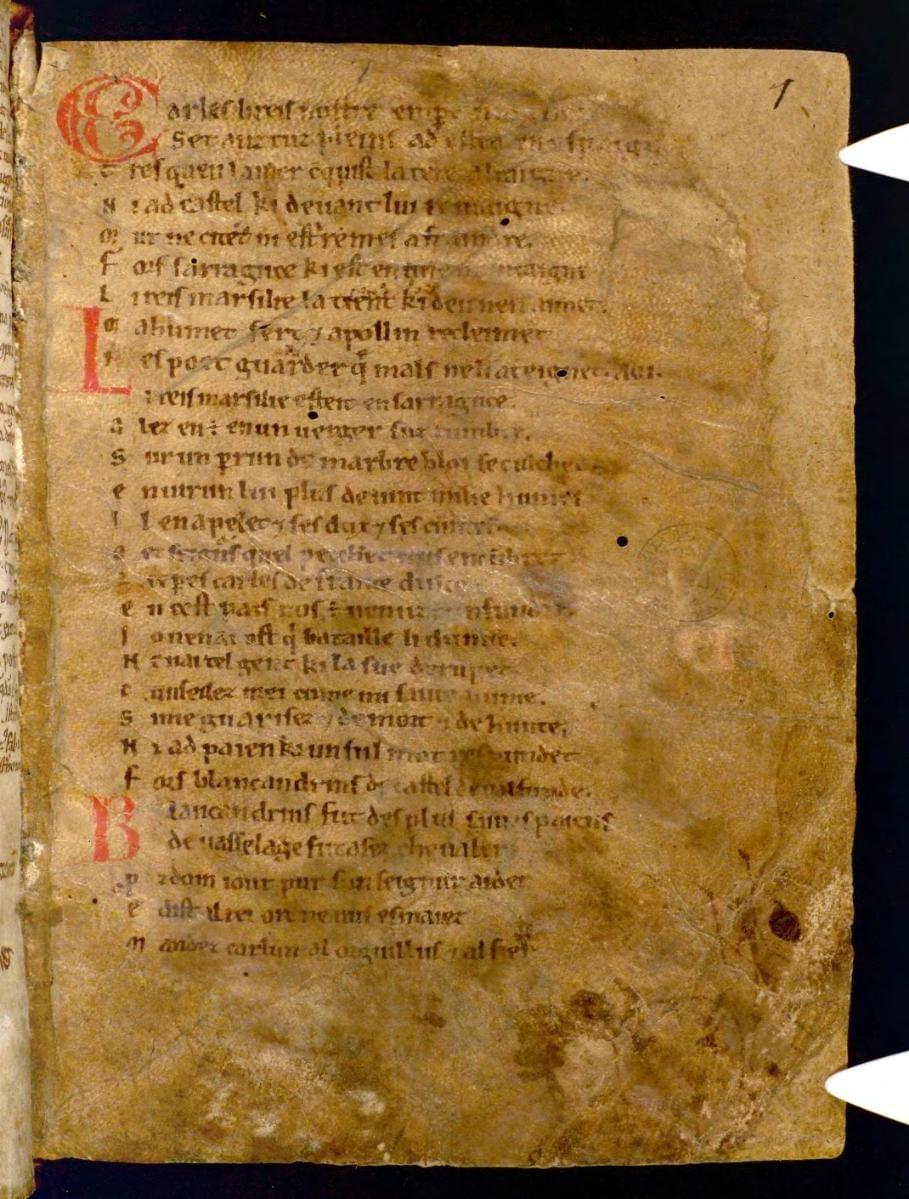

Image: Surviving Manuscript of the Song of Roland

5. To refrain from the wanton giving of offense

This essentially means to avoid deliberately offending people. The Knights of Spamalot do not abide by this rule. The Black Knight deliberately calls Arthur a homophobic slur, Arthur calls the Black Knight a ‘stupid bastard’ (63), Lancelot calls Herbert’s father a ‘bastard’ (87), Robin calls Tim a ‘sod’ and a ‘tit’ (98). So overall, the Knights of Spamalot don’t appear to abide by this rule of not intentionally offending others.

7. To fight for the welfare of all

The only character who intentionally fights for the welfare of another is Lancelot when he saves Herbert. They seek the grail only to appease God. Bedevere creates the rabbit solely to attack the French. Robin couldn’t fight off his own shadow. Galahad is never seen doing anything heroic, besides looking dashing. Arthur is just out for himself. With Herbert, Lancelot selflessly tells the Father to bugger off and let his son live his life.

8. To obey those placed in authority

The Knights do obey God when he yells at them to find the grail. Other than that, authority doesn’t mean much in the world of Spamalot. Robin runs off despite Arthur’s commands to find the grail.

9. Never turn your back upon a foe

Robin runs off at the mere sight of the Black Knight. The Knights run off after the French Taunters throw the cow at them. So they are cool with running away when things get tough.

Works Cited:

Alchin, Linda "Medieval Code of Chivalry" http://www.ancientfortresses.org/medieval-code-chivalry.htm

Owen, D.D.R (Translator) "The Song of Roland" The Boydell Press https://www.ling.upenn.edu/~rnoyer/courses/103/Owen1990.pdf